Monday, 23 January 2012

Our Lord in the Attic: Amsterdam's secret church

Wednesday, 8 June 2011

Monday, 10 September 2007

Pilgrim with a price on his head

What will you give us," they asked, with a predictable lack of spirituality, "for each one we find?"

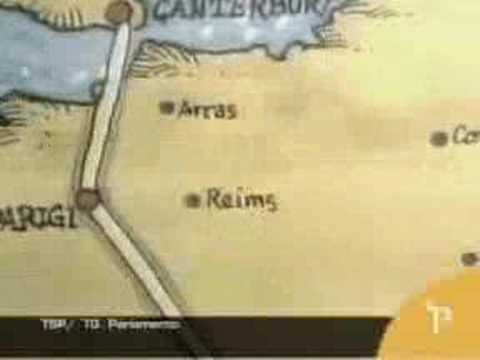

How do you put a price on the head of a pilgrim? The countless men and women who, throughout the Middle Ages, tackled the Via Francigena

, the rough and dangerous road that took them from Canterbury right across France and northern Italy to the Holy City, had risked their lives to make this journey, For them, this was virtually the highway to Heaven. What was that worth in monetary terms? I thought hard.

, the rough and dangerous road that took them from Canterbury right across France and northern Italy to the Holy City, had risked their lives to make this journey, For them, this was virtually the highway to Heaven. What was that worth in monetary terms? I thought hard."How about 1,000 lira each?" I asked, trusting that the children would not convert the sum into sterling and scorn my offer of 30p.

The deal was done. Now that pilgrims had a price on their heads, our journey had acquired fascination even for a seven-year-old and a 10-year old.

It was actually something of a miracle that we could follow the pilgrims' footsteps across a swath of northern Italy. Unlike the Pilgrims' Way through Kent, which had remained well marked and well used down the centuries, the Via Francigena disappeared a coupe of hundred years ago.

It has been rediscovered, thanks to a 10th-century Archbishop of Canterbury called Sigeric. He had to make the journey to Rome in the year 990, to receive from the Pope the symbolic pallium, the woollen stole work by archbishops. He recorded the 79 stopping places on his journey. That record, preserved in the British Museum, has made it possible for modern-day pilgrims to retrace his route.

our pilgrim hunt bean in the ancient town of Fidenza, at which point the Via Francigena swings south, skirting Parma, and races for Tuscany. Fidenza was a place of pilgrimage in itself, because of the fate of San Donnino, a martyr who, having converted to Christianity, fled the court of the Emperor Maxmimian, but was caught and decapitated in AD 291 on the banks of the city's River Stirone. Donnino managed to pick up his severed head and carry it to the opposite bank.

One of the miracles which which he was credited occurred when the bridge named after him, the Ponte di San Donnino, collapsed under the weight of a crush of pilgrims and yet none was injured. The event is faithfully recorded on the facade. So many pilgrims were shown falling into the water and then emerging on the bank that I had to negotiate a group rate of 5,000 lira with the children. Already I could see that pilgrimage can be an expensive business.

Entering the cathedral between the figures of two snarling lions - their fierceness tempered by the fact that they look more like tortoises in cardigans than kins of the jungle - we found the bones of San Donnino himself. They lie, with the severed skull placed on his chest, in an open-sided, 3rd century Roman sarcophagus in the crypt. The children crouched on the floor and peered in.

The Via Francigena passes alongside the cathedral and on through the heart of Fidenza. From there, it zig-zags south across the flat country to Fornovo, a market town beside the River Taro.

The landscape changes swiftly. The flat plains give way to mountains within an hour. Fornovo, where the road swings across the River Taro on a long low bridge, is the halfway point. In the riverbed, stumps of dark rock like standing stones show the line of the Roman bridge that the pilgrims used.

On the facade of the parish church of Santa Maria Asunta is another statue of a pilgrim. He has kept his basket, his keys and his staff, but has lost his head. I tried to negotiate a discount with the children, but without success.

At modern-day pilgrim might stop at the Touring Pub round the corner on the Via Vittoria Veneto, a concrete affair like a 1950s bus station, which offers Kilkenny Bitter.

From Fornovo, the land climbs up the valley of the River Sporzana until, at Bardone - little more than a group of houses gathered around a hilltop crossroads - it brings you to the church of Santa Maria. It was locked when we arrived, but a woman suddenly appeared with the key.

Inside, we came upon the statue of San Rocco. Passing through this area as a pilgrim and finding that many of the inhabitants had the plague, he nursed them devotedly, until succumbing to the disease himself. His statue was crowned with a halo, there was a fresh wound on his left thigh and he was accompanied by a little dog that carried a hunk of brad in its mouth. The wound symbolised his disease and the dog represented a faithful pent that brought him food daily once he had withdraw to the woods to die.

We lit a candle to him, hence qualifying for his protection against plague, leprosy and all manner of nasty skin diseases.

From here, the direct route is now a main road which, although it is not busy, is less congenial than the narrow that lane that clings to the side of the adjacent valley of the River Baganza. The scenery is dramatic now, with snowcapped mountains above, the roaring river below and, alongside us, the jagged, zig-zagging, exposed strata of the rock.

In Berceto, which was the final significant stopping place before the pilgrims crossed the Apennines,m the repaved Via Francigena passes right through the medieval town and past the door of the cathedral.

This was the most dramatic of all the churches we encountered. Inside, it was dark and unadorned, the stout grey pillars fading into the gloom. As my eyes became accustomed to the darkness, I made out a startlingly lifelike - or rather deathlike - sight. In a halo of light and flowers lay a painted statue fo the dead Christ, dressed in a cream shroud open at the chest. This was a profoundly sombre and atmospheric place.

Our journey was close to its climax as we made the final climb up to the Cisa Pass which, at 3,400ft, is the gateway through the Apennines to Tuscany and the road south to Rome.

Modern travellers have the option of taking the autostrada which, with all of the audacity with which Italians build their motorways, crosses high above the valley floor in double-decker formation, one carriageway beneath the other, then burrows beneath the pass to emerge at a modest elevation on the other side.

That was not for us. We wound our way up through the chestnut woods to the silent village of Corchia, the last point of habitation before the pass. This is an authentic enough medieval village to satisfy the most exacting of historic drama producers. The main street is too narrow for the tiny Fiats that can get everywhere else in Italy. Corchia even spurns the traditional decoration on its houses - ochre or mustard-painted rendering and dark green shutters - in favour of plain grey stone and slate.

Corchia, which until 1943 was an iron and copper mining village, feels as though it clings to the very edge of the world. Which is how it must have struck the pilgrims, all those centuries ago, when, with staff, keys and a few worldly possessions on their backs, they passed through here, stood at the narrow eminence of the Cisa Pass and looked down on the warm Tuscan hills flowing invitingly south.

Today, of course, we could have climbed into the car and been in Rome before the pilgrims were on level ground again. But we turned back. The road beyond would be a whole new journey. Besides, with the price of pilgrims being what it is, I could not afford to go any further.

Sunday, 12 August 2007

Waterloo Sunset

Ok, here's a pop-quiz question. As long as I gaze on

Yes, I am in paradise.

Quite, it keeps flowing into the night.

A girl is asked "Who are you waiting for." And replies: "The man who wrote Waterloo Sunset. I've been in the bar at the

I find the Davies family home, 6

And it was here that, in 1964, Ray and his brother and fellow Kink Dave worked out the chords to You Really Got Me, the song that first put them at the top of the charts in August 1964.

The Clissold Arms is a real Kinks find. The large back bar has a display of Kinks memorabilia. Among them is a signed copy of the Kinks first single, Long Tall Sally, a guitar, a wall of photographs and a small brass plaque which reads:

Site of 1957 performing debut of

Ray and Dave Davies

Founding members of the Kinks.

"Mum would shout and scream when dad would come home drunk,

When she'd ask him where he'd been, he said 'Up the Clissold Arms',

Chattin' up some hussy, but he didn't mean no harm."

On my way up Fortis Green I had passed the home Ray bought when he got married. No. 87 is a large white-painted detached Victorian villa set back from the road with a gravel drive. He lived here in the late Sixties and early Seventies with Rasa, who he met when she was still a

Their schools were here, too.

I head off east into Muswell Hill, down

Where Sainsbury's now stands was once the Athenaeum, a dance hall that featured in the song Come Dancing. Athenaeum Place is still there alongside it, like a Ray Davies vignette - with a beggar on the corner, and rutted cobbles leading to a former orange brick Victorian church that is now an O'Neill's Irish bar.

I walk down Priory Road where the ground falls away and London is at your feet, first the trees and terraces of the lesser houses in the valley, then the City's tower blocks and Wren churches, finally Canary Wharf, grey and blinking in the winter sunlight

I'm headed for the last outpost on my Kinks tour: their recording studios, Konk, on

Lakes and monsters

Holidaying with children goes through four phases. The first is when they are too young to voice an opinion on where you go or what you do. This is bliss, though not as much bliss as not having the little bundles of joy along in the first place.

The second is when you surrender your choices for theirs - the years of buckets and spades, theme parks, theme restaurants, Disney and Centreparcs. A chance for the adults to have a horrible time, and generally get in their revenge early for phase three.

For phase three is when the children will complain loudly that they are having the horrible-est time. Ever. In the whole history of horrible.

These are the years when you try to assert yourself and your adult tastes, in the inevitably futile hope of interesting them in things that you like, so you might begin to edge tentatively towards that great unreachable goal - the family holiday in which there is something to please everyone.

The fourth is that merciful stage when they refuse to come on your sad holidays in any case.

We are at phase three. Indeed, we seem to have been stuck at phase three for some time. Possibly for ever.

We decided to introduce our 12 and nine-year-olds to the

We would go cycling, we told them, on peaceful lanes and remote bridle paths, we would scramble up the fells for the exhilaration of hours spent walking on top of the world, from lake to shining lake.

And they replied: No we won't.

The north western corner of the

We decided to break the children in gently. For our first cycle ride I took the two of them on an easy seven mile glide down from Cockermouth to Loweswater.

Swooping down the valley, with the green hills rising to enclose us as we approached the lake, it was not a bad introduction. But the ride was not without interruption. There were halts for water. For the removal of sweatshirts. For the replacement of sweatshirts. For the removal of helmets to facilitate the scratching of heads. For the adjusting of helmets which had not been replaced correctly by father but had instead been jammed back on, trapping ears.

Then came a standoff, when an alleged asthma attack had the 12-year-old wheezing most effectively at the top of a gentle incline. But it wasn't asthma. It was just breathlessness. Something today's sedentary child is entirely unfamiliar with.

But it was the incident of The Spider On The Handlebars that made me abandon the softly-softly approach.

Squealing in terror, the arachnophobe nine-year old released his hold on his bike, veered into the hedge and went flying off, narrowly missing a Larry Grayson lookalike who was busy dusting his gate.

Lookalike-Larry was entirely in sympathy with the children's perception of this as a crisis, and for his benefit I was solicitous. But I decided that from now on it would be No More Mr Nice Dad.

Next day we tried a hike, from Buttermere, around Crummock Water and striding up the fell-side to the spectacular 170 ft waterfall of Scale Force. It was a tough walk over rough and boggy ground, chosen to really give them something to moan about.

Perversely, they loved it.

They enjoyed it most when the path petered out, the ground became boggy, and there was much teetering on rocks and stumbling through marsh, with several bootfulls each of black, brackish water.

On the way back the children announced that walks were OK as long as they were over bogs, and if I fell in at least once.

In that case, I announced, tomorrow we would try mountain climbing.

OK, at 2,159ft Whiteless Pike is not exactly Everest. But it looked like it to the children, as we set off from the shores of Crummock Water and they had to tilt their heads way back to look up to its pyramid peak.

When we hit the relentlessly-rising ridge there were complaints. But it was no good asking for food or water, because we had purposely left every form of sustenance in the car. There might be treats, but later, and they would have to be earned.

The children found the climb tough, as anyone but the superfit would. But each time they stopped and turned to look back, they found the view got better and better, and the sense of achievement grew. They most enjoyed the bits of steep exposed rock which had to be tackled with hands as well as feet.

There was one protest, however, when the puffing 12-year-old asked:

"What's the number of that emergency hot line?"

"What, Childline?"

Presumably the complaint would have been "My parents are making me climb a mountain and I think the effort will kill me."

But, fortuitously, mobile phones do not work in this corner of the

Things went swimmingly once the children treated the climb as a game, adapting one of their favourite ways of making a journey pass - laughing at people in other cars - to laughing at other walkers. There was plenty of scope. With their nobbly white knees, billowing shorts, beany hats and prawn-pink complexions, fell walkers are not exactly sex on legs.

And as they climbed towards the summit, they began to savour their achievement, delighted to find they could look way across to the

Indeed, looking down on the lane that winds up from Buttermere and through the pass at Newlauds Haus before dipping down to Derwent Water, they were indignant to see that it was possible to park there, at an altitude of over 1,000ft, and gain the fell tops with far less exertion than it had taken us to get there.

When we reached the top, I was convinced we had a pair of

"Nah" they said in unison.