What will you give us," they asked, with a predictable lack of spirituality, "for each one we find?"

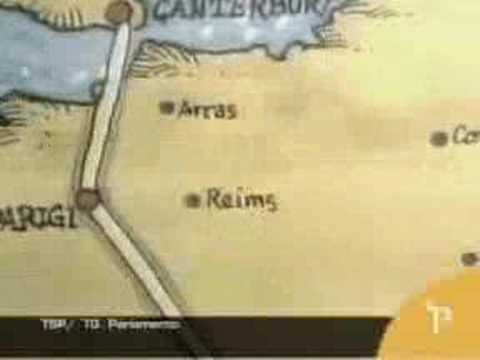

How do you put a price on the head of a pilgrim? The countless men and women who, throughout the Middle Ages, tackled the Via Francigena

, the rough and dangerous road that took them from Canterbury right across France and northern Italy to the Holy City, had risked their lives to make this journey, For them, this was virtually the highway to Heaven. What was that worth in monetary terms? I thought hard.

, the rough and dangerous road that took them from Canterbury right across France and northern Italy to the Holy City, had risked their lives to make this journey, For them, this was virtually the highway to Heaven. What was that worth in monetary terms? I thought hard."How about 1,000 lira each?" I asked, trusting that the children would not convert the sum into sterling and scorn my offer of 30p.

The deal was done. Now that pilgrims had a price on their heads, our journey had acquired fascination even for a seven-year-old and a 10-year old.

It was actually something of a miracle that we could follow the pilgrims' footsteps across a swath of northern Italy. Unlike the Pilgrims' Way through Kent, which had remained well marked and well used down the centuries, the Via Francigena disappeared a coupe of hundred years ago.

It has been rediscovered, thanks to a 10th-century Archbishop of Canterbury called Sigeric. He had to make the journey to Rome in the year 990, to receive from the Pope the symbolic pallium, the woollen stole work by archbishops. He recorded the 79 stopping places on his journey. That record, preserved in the British Museum, has made it possible for modern-day pilgrims to retrace his route.

our pilgrim hunt bean in the ancient town of Fidenza, at which point the Via Francigena swings south, skirting Parma, and races for Tuscany. Fidenza was a place of pilgrimage in itself, because of the fate of San Donnino, a martyr who, having converted to Christianity, fled the court of the Emperor Maxmimian, but was caught and decapitated in AD 291 on the banks of the city's River Stirone. Donnino managed to pick up his severed head and carry it to the opposite bank.

One of the miracles which which he was credited occurred when the bridge named after him, the Ponte di San Donnino, collapsed under the weight of a crush of pilgrims and yet none was injured. The event is faithfully recorded on the facade. So many pilgrims were shown falling into the water and then emerging on the bank that I had to negotiate a group rate of 5,000 lira with the children. Already I could see that pilgrimage can be an expensive business.

Entering the cathedral between the figures of two snarling lions - their fierceness tempered by the fact that they look more like tortoises in cardigans than kins of the jungle - we found the bones of San Donnino himself. They lie, with the severed skull placed on his chest, in an open-sided, 3rd century Roman sarcophagus in the crypt. The children crouched on the floor and peered in.

The Via Francigena passes alongside the cathedral and on through the heart of Fidenza. From there, it zig-zags south across the flat country to Fornovo, a market town beside the River Taro.

The landscape changes swiftly. The flat plains give way to mountains within an hour. Fornovo, where the road swings across the River Taro on a long low bridge, is the halfway point. In the riverbed, stumps of dark rock like standing stones show the line of the Roman bridge that the pilgrims used.

On the facade of the parish church of Santa Maria Asunta is another statue of a pilgrim. He has kept his basket, his keys and his staff, but has lost his head. I tried to negotiate a discount with the children, but without success.

At modern-day pilgrim might stop at the Touring Pub round the corner on the Via Vittoria Veneto, a concrete affair like a 1950s bus station, which offers Kilkenny Bitter.

From Fornovo, the land climbs up the valley of the River Sporzana until, at Bardone - little more than a group of houses gathered around a hilltop crossroads - it brings you to the church of Santa Maria. It was locked when we arrived, but a woman suddenly appeared with the key.

Inside, we came upon the statue of San Rocco. Passing through this area as a pilgrim and finding that many of the inhabitants had the plague, he nursed them devotedly, until succumbing to the disease himself. His statue was crowned with a halo, there was a fresh wound on his left thigh and he was accompanied by a little dog that carried a hunk of brad in its mouth. The wound symbolised his disease and the dog represented a faithful pent that brought him food daily once he had withdraw to the woods to die.

We lit a candle to him, hence qualifying for his protection against plague, leprosy and all manner of nasty skin diseases.

From here, the direct route is now a main road which, although it is not busy, is less congenial than the narrow that lane that clings to the side of the adjacent valley of the River Baganza. The scenery is dramatic now, with snowcapped mountains above, the roaring river below and, alongside us, the jagged, zig-zagging, exposed strata of the rock.

In Berceto, which was the final significant stopping place before the pilgrims crossed the Apennines,m the repaved Via Francigena passes right through the medieval town and past the door of the cathedral.

This was the most dramatic of all the churches we encountered. Inside, it was dark and unadorned, the stout grey pillars fading into the gloom. As my eyes became accustomed to the darkness, I made out a startlingly lifelike - or rather deathlike - sight. In a halo of light and flowers lay a painted statue fo the dead Christ, dressed in a cream shroud open at the chest. This was a profoundly sombre and atmospheric place.

Our journey was close to its climax as we made the final climb up to the Cisa Pass which, at 3,400ft, is the gateway through the Apennines to Tuscany and the road south to Rome.

Modern travellers have the option of taking the autostrada which, with all of the audacity with which Italians build their motorways, crosses high above the valley floor in double-decker formation, one carriageway beneath the other, then burrows beneath the pass to emerge at a modest elevation on the other side.

That was not for us. We wound our way up through the chestnut woods to the silent village of Corchia, the last point of habitation before the pass. This is an authentic enough medieval village to satisfy the most exacting of historic drama producers. The main street is too narrow for the tiny Fiats that can get everywhere else in Italy. Corchia even spurns the traditional decoration on its houses - ochre or mustard-painted rendering and dark green shutters - in favour of plain grey stone and slate.

Corchia, which until 1943 was an iron and copper mining village, feels as though it clings to the very edge of the world. Which is how it must have struck the pilgrims, all those centuries ago, when, with staff, keys and a few worldly possessions on their backs, they passed through here, stood at the narrow eminence of the Cisa Pass and looked down on the warm Tuscan hills flowing invitingly south.

Today, of course, we could have climbed into the car and been in Rome before the pilgrims were on level ground again. But we turned back. The road beyond would be a whole new journey. Besides, with the price of pilgrims being what it is, I could not afford to go any further.